DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A:Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

Headquarters United States Marine Corps

Washington, D.C. 20380-1775

4 October 1996

FOREWORD

This doctrinal publication describes a theory and philosophy

of command and control for the U.S. Marine Corps. Put very

simply, the intent is to describe how we can reach effective

military decisions and implement effective military actions

faster than an adversary in any conflict setting on any scale.

In so doing, this publication provides a framework for all

Marines for the development and exercise of effective com-

mand and control in peace, in crisis, or in war. This publica-

tion represents a finn commitment by the Marine Corps to a

bold, even fundamental shift in the way we will view and deal

with the dynamic challenges of command and control in the

information age.

The Marine Corps' view of command and control is based

on our common understanding of the nature of war and on our

warfighting philosophy, as described in Fleet Marine Force

Manual 1, Warfighting (to be superseded by Marine Corps

Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting). It takes into account

both the timeless features of war as we understand them and

the implications of the ongoing information explosion that is

a consequence of modern technology. Since war is fundamen-

tally a clash between independent, hostile wills, our doctrine

for command and control accounts for animate enemies ac-

tively interfering with our plans and actions to further their

own aims. Since we recognize the turbulent nature of war, our

doctrine provides for fast, flexible, and decisive action in a

complex environment characterized by friction, uncertainty,

fluidity, and rapid change. Since we recognize that equipment

is but a means to an end and not the end itself, our doctrine is

independent of any particular technology. Taking a broad

view that accounts first for the human factors central in war,

this doctrine provides a proper framework for designing, ap-

praising, and deploying hardware as well as other components

of command and control support.

This doctrinal publication applies across the full range of

militaiy actions from humanitarian assistance on one extreme

to general war on the other. It applies equally to small-unit

leaders and senior commanders. Moreover, since any activity

not directly a part of warfighting is part of the preparation for

war, this doctrinal publication is meant to apply also to the

conduct of peacetime activities in garrison as well as in the

field.

This publication provides the authority for the subsequent

development of command and control doctrine, education,

training, equipment, facilities, procedures, and organization.

This doctrinal publication provides no specific techniques or

procedures for command and control; rather,

it provides

broad guidance which requires judgment in application. Other

publications in the command and control series will provide

specific tactics, techniques, and procedures for performing

various tasks. MCDP 5,

Planning, discusses

the planning side

of command and control more specifically.

"Operation VERBAL IMAGE," the short sto!y with which

this publication begins, offers a word pictUre of command and

control in action (done well and done poorly) and illustrates

various key points that appear in the text. It can be read sepa-

rately or in conjunction with the rest of the text. Chapter 1

works from the assumption that, in order to develop an effec-

tive philosophy of command and control, we must first come

to a realistic appreciation for the nature of the process and its

related problems and opportunities. Based on this understand-

ing, chapter 2 discusses theories of command and control,

looking at the subject from various aspects, such as leader-

ship, information management, and decisionmaking. Building

on the conclusions of the preceding chapters, chapter 3 de-

scribes the basic features of the Marine Corps' approach to

command and control.

A main point of this doctrinal publication is that command

and control is not the exclusive province of senior command-

ers and staffs: effective command and control is the responsi-

bility of all Marines. And so this publication is meant to guide

Marines at all levels of command.

DISTRIBU11ON: 142 000001 00

© 1996 United States Government as represented by the Sec-

retary of the Navy. All rights reserved.

Corps

MCDP 6

Command and Control

Operation VERBAL

IMAGE

Chapter 1.

The Nature of Command and Control

How Important is Command and Control? —

What is

Command and Control? —

What is the Basis of Command

and Control? — What

is the Relationship Between

"Command" and "Control"? —

What Does it Mean to be

"In Control"? — Complexity

in Command and Control —

What Makes Up Command and Control? — What

Does

Command and Control Do? —

The

Environment of

Command and Control: Uncertainty and Time —

Command and Control in the Information Age —

Conclusion

Chapter 2. Command and Control Theory

Point of Departure: The OODA Loop —

The

Information

Hierarchy — Image Theory — The Command and Control

Spectrum —

Leadership Theory — Planning

Theory —

Organization Theory — Communications Theory —

Information

Management Theory — Decisiomnaking

Theory — Conclusion

Command and Control

MCDP 6

Chapter 3.

Creating Effective Command

and Control

The Challenges to the System — Mission Command and

Control — Low-Level Initiative — Commander's Intent —

Mutual

Trust — Implicit Understanding and

Communication — Decisionmaking — Information

Management —

Leadership — Planning

— Focusing

Command and Control —

The Command and Control

Support Structure — Training, Education, and Doctrine —

Procedures

—

Manpower — Organization

— Equipment

and Technology — Conclusion

Notes

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

Scene: A troubled corner of the globe, sometime in the near

future. The Marine expeditionary force prepares for an up-

coming offensive.

2248 Monday: Maj John Gustafson had taken over as the

regimental intelligence officer just in time for Operation

VERBAL IMAGE. Who thinks up the names for these opera-

tions anyway? he wondered. This would be his first command

briefing and he wanted to make a good impression. The colo-

nel had a

reputation

for

being a tough, no-nonsense

boss—and the best regimental commander in the division.

Gustafson would be thorough and by-the-numbers. He would

have all the pertinent reports on hand, pages of printouts con-

taining any piece of data the regimental commander could

possibly want. He went over his briefing in his mind as he

walked with his stack of reports through the driving rain to

the command tent.

Command and Control

MCDP 6

The colonel arrived, just back from visiting his forward

battalions and soaking wet, and said, "All right, let's get

started. S-2, you're up."

Gustafson cleared his throat and began. He had barely got-

ten through the expected precipitation when the colonel held

up his hand as a signal to stop. Gustafson noticed the other

staff officers smiling knowingly.

"Listen, S-2," the colonel said, "I don't care about how

many inches of rainfall to expect. I don't care about the per-

centage of lunar illumination. I don't want lots of facts and

figures. Number one, I don't have time, and number two, they

don't do me any good. What I need is to know what it all

means. Can the Cobras fly in this stuff or not? Will my tanks

get bogged down in this mud? Don't read me lists of enemy

spottings; tell me what the enemy's up to. Get inside his head.

You don't have to impress me with how much data you can

collect; I know you're a smart guy, S-2. But I don't deal in

data; I deal in pictures. Paint me a picture, got it?"

"Don't worry about it, major," the regimental executive of-

ficer said later, clapping a hand on Gustafson's shoulder.

"We've all been through it."

0615 Tuesday: The operation was getting underway. In his

battalion command post, LtCol Dan Hewson observed with

satisfaction as his units moved out toward their appointed ob-

jectives. He watched the progress on the computer screen be-

fore him. Depicted on the 19-inch flat screen was a color map

of the battalion zone of action. The map was covered with

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

luminous-green unit symbols, each representing a rifle pla-

toon or smaller unit. If a unit was stationary, the symbol re-

mained illuminated; when the unit changed location by a

hundred meters, the symbol flashed momentarily.

Hewson tapped on a unit symbol on the touch screen with

his finger, and the unit designator and latest strength report

came up on the screen. Alpha Company; they should be mov-

ing by now.

"Get on the hook and find out what Alpha's problem is,"

Hewson barked. "Tell them to get moving."

With rapid ease he "zoomed" down in

scale from

1:100,000 to 1:25,000 and centered the screen on Bravo Com-

pany's zone. Hewson prided himself on his computer literacy;

no lance corporal computer operator necessary for this old

battalion commander, he mused. Hewson was always amazed

at the quality of detail on the map at that scale; it was practi-

cally as if he were there. That was the old squad leader in him

coming out. He tapped on the symbol of Bravo's second pla-

toon as it inched north on the screen.

No, they should turn right at that draw, he said to himself.

That draw's a perfect avenue of approach. Where the hell are

they going? Don 't they teach terrain appreciation anymore

at The Basic School?

"Get Bravo on the line," he barked. "Tell them I want sec-

ond platoon to turn right and head northeast up that draw.

Now. And tell them first platoon needs to move up about 200

yards; they're out of alignment."

Satisfied that everything was under control in Bravo's

zone, Hewson scrolled over to check on Charlie Company.

Command and Control

MCDP 6

Back when he was a young corporal, some 22 years ago, this

technology didn't exist. It was amazing how much easier

command and control was today compared to his old squad

leader days, how much more control there was now. He won-

dered if the junior Marines realized just how lucky they were.

0622 Tuesday: Second Lieutenant Rick Connors was feeling

anything but lucky. Justpast the mouth of a draw, he angrily

signaled for second platoon to halt. Company was on the ra-

dio, barking about something. He was wet, he was cold; his

rain top had somehow sprung a leak, and a stream of icy wa-

ter poured down his spine. And on top of everything else,

now this.

"Come again?" he said to his radio operator.

"Sir, Hotel-3-Mike says we're supposed to turn right and

head up this draw," LCp1 Baker repeated.

Damn PLRS, Connors cursed to himself. He had never ac-

tually seen a PLRS, that venerable piece of equipment having

been replaced by a newer, lighter generation of position-

locating system which attached to any field radio and sent an

updated position report every time the transmit button was

cued. But like all the more experienced Marines, he insisted

on calling the new equipment by the old name.

"Up that draw," Connors repeated, as if to convince him-

self he had heard correctly.

"Hotel-3-Mike says it's an excellent avenue of approach,

sir," Baker reported dutifully.

MCDP 6

- Operation VERBAL IMAGE

Connors studied the impenetrable web of thorny, interlock-

ing undergrowth in the draw and snorted scornfully. Maybe

on somebody's computer screen it is, he

thought. But on the

ground it's not. Somebody at battalion must have his map on

1:25,000 again. So much for the decentralized mission con-

trol they told us about at TBS. What do they even need lieu-

tenants for f they're going to try to control us like puppets?

He

despised the prospect of hacking his way through the thick

brush of the draw, especially when first squad had spotted

what looked like an excellent concealed avenue of approach

not 200 yards ahead. Of course, if he followed Instructions,

higher headquarters would be squawking about his slow rate

of advance—there were no thickets of pricker bushes on a

computer map. He could just imagine the radio message:

"What's

taking you so long, 3-Mike-2?

It's

only an inch on

the map." And

if he chose the other route they'd be on him in

no time about disobeying orders. He cursed the PLRS again.

But then he decided it wasn't the PLRS that was the problem;

it was the way it was being used.

1118 Tuesday:

A section of SuperCobra Ills churned

through the driving rain on its way back to the abandoned

high school campus that served as an expeditionary airfield,

returning from an uneventful scouting mission.

"I'll tell you what, skipper," 1 stLt Howard Coble said from

the front seat of the lead helicopter, "this soup isn't getting

any better."

Command and Control

MCDP 6

In fact, it was getting considerably worse, Capt Jim Knut-

sen decided as he piloted the buffeting attack helicopter. A

squall was moving back in. Goo at 500 feet, visibility down

inside a mile and worsening.

"I'm glad I'm not those poor bastards," Coble said, indica-

ting a mechanized column on the muddy trail below them to

starboard.

"You got that right," Knutsen said, not paying much atten-

tion.

Until Coble cursed sharply.

"Those aren't ours," Coble said. "Take a look, skipper.

BMPs, T-80s."

Coble was dead right. What they were looking at was an

enemy mechanized column, Knutsen guessed, of at least bat-

talion strength. Probably more. His first instinct was to make

a run at the column, but his intuition told him otherwise.

Something was not right. Knutsen banked the Cobra away

sharply to avoid detection, and his wingman followed.

What's wrong with this picture? Knutsen said to himself.

The mission briefing had said nothing about enemy mecha-

nized forces anywhere near this vicinity. The enemy had ap-

parently used the cover of the bad weather to move a sizable

force undetected through a supposed "no-go" area into the di-

vision's zone. Knutsen was familiar enough with the ground

scheme of maneuver to know instantly that this unexpected

presence posed a serious threat to the upcoming operation.

We got ourselves a major problem. These guys are not sup-

posed to be here.

MCDP 6 Operation VERBAL IMAGE

His wingman's voice crackled over the radio: "Pikeman,

did you see what I just saw at two o'clock?"

"Roger, Sylvester."

"We need to let DASC know about this," Coble said on the

intercom.

Knutsen considered the problem. Reporting the sighting to

the direct air support center would, of course, be the standard

course. But because of the weather, they'd had trouble talking

to the DASC all day; they couldn't get high enough to get a

straight shot. In these conditions, he figured they were nearly

a half hour from the field. And when he finally got the mes-

sage through, he could imagine the path the information

would take from the DASC before it reached the units at the

front—and that was provided they even believed such an un-

likely report. DASC hell, we need to tell the guys on the

ground, he thought. They might like to know about an enemy

mech column driving straight through the middle of the

MEF's zone. Forget normal channels. Unfortunately he had

no call signs or frequencies for any of the local ground units.

"Howie, find me some friendlies on the ground," he said.

He radioed his wingman with his plan.

"Got somebody, skipper," Coble said shortly. "AAV in the

tree line at nine o'clock. Got it?"

"Roger, I'm setting down."

1132 Tuesday:

You got to be crazy to be flying in this

weather, Capt Ed Takashima said to himself when he heard

the sound of approaching helicopter rotors. He was twice

7

Command and Control

MCDP 6

amazed to see the Cobra appear low over the trees and settle

into the clearing not a hundred yards away while its partner

circled overhead. He hopped down from his AAV and jogged

out into the clearing to meet the Marine emerging from the

cockpit and was three-times astonished to recognize him as

an old Amphibious Warfare School classmate.

"Knut-case," he said, pumping his friend's hand enthusias-

tically. "I should have known nobody else would be crazy

enough to fly in this stuff. What the hell are you doing here?"

Knutsen quickly explained the situation and, when he was

finished and saw Takashima's expression, said: "Don't look

at me like I'm crazy, Tak."

Anybody else Takashima would have thought was cra-

zy—or else completely lost—but not Knutsen. He had known

Knutsen too long for that. Knutsen was too squared away.

"Give me your map, I'll show you," Knutsen said. "We're

right here, right? And the enemy is right there, heading in

this direction," jabbing the map and tracing the enemy move-

ment.

As Knutsen had begun to diagram the enemy move, Taka-

shima was already considering the situation. With all the sen-

sors and satellites and reconnaissance assets that support a

MEF, Takashima wondered, how does an enemy mechanized

battalion drive through the middle of our sector without being

detected?

He remembered reading something somewhere

about uncertainty being a pervasive attribute of war. Chalk

one up to Clausewitz 's 'fog of war," Takashima decided. Of

course, Takashima knew, since it was a "no-go" area—and

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

that meant that somebody up the chain had looked at the ter-

rain and decided it was impassable—it would remain rela-

tively unobserved. But how it had happened didn't matter:

it

had happened. What to do about it? That was the problem.

Six or seven clicks, tops, he thought, looking at the map. Not

much time. This changed everything. The original battalion

plan would have to be scrapped; it was as simple as that.

Takashima recognized that his original mission was over-

come by events. He made his decision. The situation called

for quick thinking, and quicker action. The objectives might

change, but the overall aim remained the same. The ultimate

object, Takashima knew, was to locate the main enemy fotce

and attack to, destroy it. That could still be the object; it wiId

just have to happen a lot farther south than had been plan4ed.

If the battalion could make a 90-degree left turn in time, hey

might just pull it off. Now if he could just get battalion t? go

along with it . . . . he needed to talk to the battlion cpm-

mander.

Knutsen had finished tracing the enemy movement, and his

finger rested on the map, pointing at a small town called Cul-

verin Crossroads.

"That's it then," Takashima said. "Culverin Crossroads."

"I hear you, Tak," Knutsen said. "You're thinkng of that

West Africa map ex we did last year at AWS, aren't you?

The one where we wheeled the whole regiment and took the

red force in the flank."

"Yeah, that's the one," Takashima said.

9

Command and Control

MCDP 6

"What

the

hell; let's do it. I got enough fuel for maybe one

pass. You want me to work them over, or don't you want

them to know that we're on to them?"

"Let's wait and surprise them. Can you bring back some

friends?"

What a kick, Knutsen thought. A couple of captains stand-

ing in the middle of a muddy field in a downpour working out

the beginnings of a major operation. It reminded him of play-

ing pick-up football as a kid and drawing improvised plays in

the dirt.

"We'll be here," he said with a grin. "You'll recognize

me—I'll be the one in front."

"See you then, K.nut-case," Takashima said.

They shook hands, and Knutsen climbed back into the

cockpit.

"Olsen!" Takashima bellowed at his radioman. "Try to get

me battalion. 1 need to talk to the colonel direct."

1310 Tuesday:

"General, the latest weather pictures are

coming in," the lance corporal reported, the note of anxious-

ness unmistakable in his voice.

MajGen Harry Vanderwood doubted if there was a single

Marine anywhere in the wing who did not recognize the sig-

nificance that attached to the latest forecasts.

"I'll be right there, Marine," he replied.

No sooner had Vanderwood arrived in the tactical air corn-

mand center than the MEF commander bustled in unan-

nounced as he had a disconcerting habit of doing. You never

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

knew when he was going to show up, or where, Vanderwood

mused. Wing commander or mechanic on the flight line, you

were never safe.

"Have you gotten the latest on the situation, Harry?" the

MEF commander asked.

"As of the last 15 minutes, general," Vanderwood replied.

"Not that I'm any smarter than I was before. I'd still like to

know what the hell is going on."

"That makes two of us. I'd like to talk to those Cobra pilots

myself."

"It's being arranged, general. They managed to take off on

another sortie before we could grab them. Under terrible con-

ditions, I might add. When they get back, I'm either going to

give them a medal or a butt-chewing; probably both."

The MEF

commander

grunted. "How's the weather look-

ing?" he asked.

"We're just in the process of pulling down the latest pic-

tures from the weather satellite," Vanderwood said.

A large-scale map of the area of operations appeared on the

large screen, color-coded to illustrate the precipitation fore-

cast.

"No good news there," Vanderwood said. "Let's take a

look at the incoming weather."

A broader map, much like a weather map on a television

newscast, appeared on the screen. Heavy white blotches

swept sputteringly across the screen from left to right.

"Freeze it right there," Vanderwood said, and the image

stopped moving. "Good. That could be the break we're look-

ing for. I figure in about 90 minutes we'll be able to get

Command and Control

MCDP 6

something going. If this pattern holds, I plan to blot out the

sun—what little sun there might be—with aircraft by 1500.

Now all we need is to know what we're going to be attack-

ing."

"How about cueing up the MEF situation package, and

we'll see if we can't make some sense of this," the MEF com-

mander said. "And see if we can get General Bishop on tele-

conference."

"Somebody ask the Top to come over here," Vanderwood

said, meaning the intelligence chief.

"General, the division commander's away from the CP, but

we're setting up video with the chief of staff," a Marine re-

ported.

"Very well," the MEF commander said. He fully expected

Bishop to be away from the command post; in fact, the divi-

sion command post was the last place he'd expect to find, the

division commander in the middle of a battle.

The computer operator, Cpl Beale Davis, tapped quickly

on his keyboard, and the wall-sized screen blinked, the

weather map replaced by a situation map of the MEF's area

of operations. From the menu across the top of the screen, he

opened a "conference" window, and the division chief of staff

appeared in a live video feed.

"How are you, Tom?" the MEF commander said.

"Hanging in, general," Col Tom Hester replied. "Sir, Gen-

eral Bishop has gone forward. Do you want him paged? If

he's at one of the regimental CPs, we can get him on video

too."

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

"No, that's all right. We're just going to try to piece this

picture together, and I want everybody to share the same im-

age. Are you looking at the same thing we are?"

"Yessir, he is," Davis said, meaning that the screen in the

division command post would depict the same information

and images that were being called up on the wing situation

map.

Davis had logged into the theater data base and could "pull

down" almost instantaneously any individual piece of data, or

complete or partial package of information, that had been en-

tered into the system anytime, anywhere, by any means. He

had access to text, imagery, and live or prerecorded video-and

audio, which he could call up by opening additional windows

on the screen. Through the theater data base, he had access to

State Department reports, Defense Intelligence Agency sum-

maries, Central Intelligence Agency accounts, and National

Imagery and Mapping Agency charts. Likewise, he could call

up the latest tactical reports and analyses by a variety of cate-

gories—time, unit, contents, location, reliability—and could

specify the level of information resolution— "granularity,"

they called it. Any time he asked for tactical reports over a

period of time, the software would automatically "crunch

out" a trend analysis, both in picture and bullet form. With a

little manipulation, he could get direct feeds from satellites or

aerial reconnaissance drones. (This procedure was not taught

in the classroom; it was an unauthorized "back door" gate-

way, but nobody complained when Davis pulled it off.) Per-

haps most important of all, he could access the Cable News

Network for the latest-breaking developments. There was no

13

Command and Control

MCDP 6

lack of information out there, Davis knew. You were being

bombarded by it. Any yahoo could access a near-endless flow

of impressive data. The trick to being a good computer opera-

tor was being able to sift through it all to access the right in-

formation in the right form at the right time so the old man

could

figure out what it meant.

In an effort to make some sense of the enemy situation,

they pulled down various "packages" of information, mostly

in picture form, which promptly appeared and disappeared on

the screen at Davis' command. Enemy armor spottings within

the last 48, 24, and 12 hours. All ground contacts reported in

the last 48 and 24 hours. All enemy artillery units spotted and

fire missions reported in the last 48 hours. Road and rail us-

age in the last 72 hours. Sightings of enemy mobile air de-

fense equipment, usually a good indicator of the disposition

of the main body, in the last 48 and 24 hours. Enemy radio

traffic in the last week. Enemy aviation activity in the last 2

days. Every once in a while the MEF

commander

would ask

for a "template," a computer-generated estimate of possible

enemy dispositions and movements based on the partial infor-

mation that was available. Each template automatically came

with a reliability estimate—"resolution," they called it—cal-

culated as a percentage of complete reliability. The best reso-

lution they had gotten for any one template was 45 percent;

most were in the twenties and thirties. Statistically not very

good—but certainly as good as could be expected.

Another set of red enemy symbols flashed on the screen.

"What the hell," the MEF commander said, looking at the

screen which indicated a heavy flow of enemy helicopter

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

traffic along a single route. A major

heliborne

operation? In

this weather? As if things aren 't sticky enough. And why is

this the first I'm hearing of it?

"You're telling me the en-

emy's been flying fleets of helicopters continuously the last 6

hours?"

Vanderwood looked to MSgt Edgar Tomlinson, the intel-

ligence chief.

"No, general," Tomlinson said. "He's not flying anything.

What you're seeing on the screen, believe it or not, is actually

a row of power lines. We checked it out. Radiating and blow-

ing in this wind, our sensors picked them up as helicopters."

"You're kidding me, Top," the MEF commander said

skeptically. "Our sensors think a set of power lines is a bunch

of helicopters?"

"I guarantee it, general," Tomlinson said. "If you want to

call up an aerial photo, I can show you the power lines."

"No, I believe you, Top."

"I've seen it happen before," Tomlinson said. "This gear is

great, as long as you don't trick yourself into thinking that it's

actually smart."

Despite an aggregate resolution of under 25 percent, Van-

derwood sensed that a possible pattern had slowly begun to

develop, but hardly anything conclusive. A possibility. A

hunch. A little better than a wild guess. Despite the admit-

tedly amazing technology, you could never be certain of any-

thing, Vanderwood knew. Despite the artificial intelligence,

the decision aids, the computer analysis. As long as war re-

mained a clash of human wills, Vanderwood mused, no mat-

15

Command and Control

MCDP 6

ter how much technology you had, it still boiled down in the

end to intuition and judgment.

"General, the division commander's coming in on video

link," a Marine interrupted.

A window opened on the wall screen, and MajGen Miles

Bishop appeared, apparently from inside a command AAV

somewhere on the battlefield, the trademark cigar stub

clamped in his teeth.

"Hey, can anybody hear me?" he was saying gruffly over

the background noise in the AAV. "Is this blasted thing on?"

"Bish, this is Vanderwood with the MEF commander," the

wing commander said. "You're coming in fine on this end."

"The video whatzit thing is on the blink on this end, but I

can hear you okay," Bishop replied.

"Glad you could spare a few minutes out of your busy

schelule," the MEF commander said. "We've been trying to

figure out what the hell's been going on. We've been running

some software for the last half hour, and we think we might

have something."

"You want to know what the hell's going on, general?"

Bishop said. "Hell, I can tell you what's going on."

"Okay, let us have it," the MEF commander said, and

Bishop proceeded to describe in his own colorful but accurate

way the same situation that had begun to take shape, with

much less clarity, on the wall screen of the TACC. Vander-

wood and the MEF commander exchanged glances. Bishop,

Vanderwood mused, shaking his head. What apiece of work

Glad he 's on my team.

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

"How did you come by that, Bish?" the MEF commander

asked.

"Me and a couple of the boys sitting around a heat tab

making some coffee just swagged it," Bishop said with a lop-

sided grin. "Ever-lovin' coop da oil—isn't that what you're

always calling it, Harry?"

"Coup d'oeil, Bish," Vanderwood pronounced—referring

to the French term which described the ability of gifted com-

manders to peer through the "fog of war" and intuitively

grasp what was happening on the battlefield.

"Yeah, whatever," Bishop snorted.

Vanderwood grinned at Bishop's famous good-old-boy

routine. Outside the circle of general officers, few Marines

knew that French was one of the four foreign languages that

Bishop spoke like a native.

"As long as he's got it," the MEF commander said, "let

him pronounce it however he likes."

1428 Tuesday: Capt Takashima heard the unmistakable

sound of the ATGMs firing off in unison like a naval broad-

side. The doctrinal manuals called it "massed, surprise fires."

Takashima called it "a world of hurt for the bad guys." Damn

if those bastards didn 't walk right into it, he thought as he

scampered forward to get a better look at the situation at the

crossroads where first platoon had just sprung an ambush on

the leading elements of the enemy column. I owe Knutsen a

beer when this is all over. He couldn't explain how he knew,

but just from the sound of things he could tell that first

17

Command and Control

MCDP 6

platoon had caught them pretty good. Amazing how you

learned to sense these things. The ground nearby erupted in a

massive explosion, and he hit the deck—S--or rather, the 6

inches of water that covered the deck.

"Olsen, you all right?" he yelled after checking to make

sure he was still in one piece.

"Yessir," his radioman replied. "Captain, third platoon

wants to talk to you."

Second Lieutenant Tim Dandridge, Golf Company's least

experienced platoon commander, was several hundred yards

off to the right. Takashima had originally put third platoon

where he could keep his eye on Dandridge, but when he'd

spun the company, it had left third platoon off on the right

flank by itself. Takashima switched on his headset.

"Oscar-3, this is Romeo-2-Oscar, go."

"Romeo-2-Oscar, I've got mechanized activity to my front

and more activity moving through the woods around my right

flank, over," Dandridge reported.

Even over the radio Takashima could sense the nervous-

ness in the lieutenant's voice.

"Echo's on your right flank," Takashima said.

"Roger, Romeo-2-Oscar, I don't think it's Echo," came the

reply. "I'm not picking them up on PLRS."

Takashima checked his electronic map board, networked to

Olsen's radio, which in addition to his own eight-digit loca-

tion could show the location of friendly transmitters. He

punched in a request for the location of all transmitters of pla-

toon level or higher. Dandridge was right: no Echo Company

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

units. Which meant one of two things:

either Echo was so

badly lost they weren't even on the map, or somebody had

keyed the wrong code into all of Echo's transmitters.

"Have you made contact with Echo?" Takashima asked.

"Negative. Can't raise them."

"Any visual with the enemy?"

"Negative, but they're definitely out there," Dandridge

said. "Estimate at least a company."

"Roger, are you in position yet?"

Third platoon should

have been well set in by now, ready to ambush the advancing

enemy forces.

There was a pause.

"Er, roger . .

. pretty much,

Romeo-2-Oscar," came the halting reply.

Which meant "No," Takashima knew. Good news got

passed without hesitation; bad news always seemed to move

more reluctantly. Not a good sign. For a second, he consid-

ered heading over to third platoon's position to check things

out, but he quickly dismissed the idea. His intuition still told

him the critical action was taking place in front of him at first

platoon's position. Events were still unfolding as expected,

thanks to Knut-case. This was where he needed to be.

Chances were that the young lieutenant was exaggerating; but

yet, if Dandridge was right, then Takashima had read things

wrong, and the enemy had other ideas in mind. You could

never count on the bastards doing what they were supposed

to.

"Gunny!" Takashima bellowed over the sound of the shell-

ing.

19

Command and Control

MCDP 6

A moment later GySgt Roberto Hernandez splashed down

beside him.

"Gunny, third platoon is reporting enemy activity to their

front and flank," Takashima began.

"Roger that, skipper," Hemandez said. "I was listening in."

Naturally, Takashima thought. Nothing the gunny did sur-

prised him anymore.

"I'm concerned about what's going on over there," Taka-

shima said. "But I don't have time to check it out myself.

That activity they reported might or might not be Echo Com-

pany. Gunny, I want you to hustle over there, have a look

around, and report back to me what you see. Use an alternate

net. If it's real trouble, I need to know in a hurry. Don't step

on any toes, but you might want to make a few tactful sugges-

tions if it's appropriate."

"You want me to be, sir, what is sometimes referred to in

the literature as a 'directed telescope,' "Hernandez said.

"Directed tele-what? Get outta here, gunny," Takashima

said with a grin.

Sometimes it was a pain having the best-read staff NCO in

the Marine Corps as a company gunny, he decided as he

watched Hernandez charge away. But not usually.

1455, Tuesday: "Any questions?"

Any questions? Col Perry Gorman, the division G-3, won-

dered incredulously. Where should I start?

MajGen Bishop had just spent the last half hour orienting

his staff to the new situation. He stood in front of the large

20

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

electronic mapboard in the musty tent which housed the divi-

sion's future ops section. The map was crisscrossed with the

broad arrows and symbols he had been drawing with the sty-

lus while he talked. Every once in a while Bishop would call

for an estimate or opinion, or one of his staff would ask a

question, make a recommendation, or take the stylus to sketch

on the map. An energetic discussion would usually ensue and

Bishop would let this go on for a few minutes, listening to the

arguments for and against and benignly chewing on his cigar

while the members of his staff had their say; then he would

suddenly shut the discussion off and announce his position.

Sometimes Bishop followed the advice of his staff; some-

times, Gonnan was convinced, the general had already made

his decision but wanted to make sure his people felt that they

had had the opportunity to participate. It was truly an educa-

tion watching Bishop work his staff, Gorman decided. It was

a fluid and idiosyncratic process, reflective of Bishop's own

personality. Never exactly the same twice and yet very effec-

tive. Anybody who thought staff planning was a mechanical

process had never been around MajGen Miles Bishop.

There was an old military saying, attributed to the Prussian

Field Marshal Moltke, that no plan survives contact with the

enemy. In a short period of time by merely modifying an ex-

isting branch plan, Bishop quickly reoriented the efforts of

the division to meet the new situation. Gorman's first thought

was for the wasted effort; but he quickly realized the effort

had not been wasted at all:

it had been a valuable learning

process which had resulted in an improved situational aware-

21

Command and Control

MCDP 6

ness that was shared by Bishop, the entire staff, and subordi-

nate commanders.

A feeling had engulfed the command post that through pre-

vious good planning and adaptability the division had turned

a potential crisis into a decisive opportunity. Of course, Gor-

man mused, an awful lot of things had to happen to make

adaptability during execution possible. It's amazing how

much preparation is required to provide flexibility in execu-

tion. A

division contained an awful lot of independent parts

that needed to be working toward the same goal. The inteiii-

gence collection plan would have to be reoriented to the new

axis of advance, as would the fire support planning and the

logistics effort. Potential enemy countermoves would have to

be considered, as well as possible ways to deal with them.

One good

thing that doesn 't have

to change is the com-

mander 's

intent and its end state. The

force would have to be

reorganized to support the new taskings. Fragmentary orders

would have to be issued. Necessary coordination would have

to be effected above, below, and laterally—especially with

the wing since all the aviation support requirements had

changed. The light armor battalion would have to be rede-

ployed to continue the counterreconnaissance battle. With

Task Force Hammer as well as all the forward units commit-

ted to the exploitation, a new reserve would have to be çonsti-

tuted somehow, but not immediately. Thought would have to

be given to protecting the lengthening lines of communica-

tions as the pursuit continued. The general's concept for a

regimental helicopterborne attack into the enemy rear would

have to be worked out—a major evolution in itself (although

22

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

most of the planning and coordination would be done by the

regiment). Landing zones and helicopter lanes would have to

be reconnoitered, air defenses located and targeted for sup-

pression...

"Last chance," Bishop was saying. "No saved rounds?"

"You want this by when exactly, general?" a voice from

the back of the tent asked.

Laughter broke out, and Bishop smiled but did not bother

to answer. The general's obsession with tempo was legen-

dary.

"Look, people, don't worry about trying to control every

moving piece in this monster. It's not gonna happen. I can tell

you it's gonna be chaos for the next few days at least. Maybe

longer. The battalions and regiments are already starting to do

what we need them to do, so let's not try to overcontol this

thing. I just want you to make sure that all the chaos and may-

hem are flowing in the same general direction and that we

keep it going. Coordinate what absolutely needs to be coordi-

nated and don't try to coordinate what doesn't. Keep this

thing pointed straight, but let it go. Remember, the sign of a

good plan is that it gives you both direction and flexibility.

"All right," the general concluded, "I think everybody

knows where we stand and what needs to be done. Let's get at

it."

1505 Tuesday: If 2ndLt Connors had been unhappy before,

he was positively miserable now. He decided he felt about as

useful as a mindless pawn in some giant chess game, being

23

Command and Control

MCDP 6

moved around one square at a time. Certainly don't want to

get too far ahead of ourselves, do we?

The analogy was

pretty appropriate, he thought. Too bad the chess player who

was ordering him around showed every sign of being an inde-

cisive beginner who seemed to be taking an awful lot of time

between moves.

What made things worse was that from the distant shelling

and the radio traffic he could tell that there was one heck of a

battle going on. And he was missing it. Every time he radioed

for instructions he'd get the same reply—"Wait out"—and

when the orders eventually arrived, it seemed that he was al-

ways one step too late. Usually, he'd arrive just in time to

have to duck the tail end of somebody else's fire mission. He

might just as well have been wandering around the pine for-

ests of beloved Camp Lejeune for all the action he was get-

ting. Was that a red-cockaded woodpecker he just saw?

He crawled to the edge of the vegetation and peered across

the clearing. That was the objective, alt right, some 300 yards

away. Hill 124, now known as Objective Rose after the com-

pany commander's mother-in-law. He checked his watch; the

prep fires were scheduled to commence at half past. He

searched the hilltop carefully through his thermal binoculars

and saw no sign whatsoever of enemy activity.

Of course, he didn't know what he had expected to see.

He'd been given no information on the enemy situation on the

objective, and he had no idea why he was attacking this hill in

the first place. He certainly had no idea what made Hill 124

so important—-other than that it was a convenient place to

draw a goose egg on some higher-up's map. He was expected

24

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

to attack and seize Objective Rose, commencing at 1530, and

that was that.

With his squad leaders, Connors crawled back to rejoin the

platoon.

"Lieutenant, company wants to talk to you," his radioman

reported.

Connors switched on his headset.

"Hotel-3-Mike, this is 3-Mike-2," he said.

"3-Mike-2, are you ready yet?"

For about the tenth time, Connors said to himself. Keep

your shorts on; the attack doesn 'I go

for another 20 minutes.

"Roger that," he replied out loud. "The objective is de-

serted."

"Roger. The prep fires commence at 1530, as scheduled,

and last for 5 mikes."

"I say again, the objective is deserted, Hotel-3-Mike,"

Connors said. "We don't need the prep fires; we can just walk

up on the objective."

There was a pause. Connors could imagine the captain

wrestling with that one. He couldn't blame the captain, really.

Battalion wanted things done a certain way. To change things

now, Connors knew, would throw off the timetable and would

mean shutting off the scheduled fires—in short, it would dis-

rupt the plan. And you certainly didn't want to interfere with

the plan, he knew—not in this battalion anyway. The plan

was everything. All the elements of the battalion were sup-

posed to attack in close synchronization, Connors knew—

"synchronization" was LtCol Hewson's favorite buzzword.

Of course, when Connors thought of synchronization he

25

Command and Control

MCDP 6

invariably thought of synchronized swimming, and he smiled

at the ridiculous image of a couple of swimmers pirouetting

in graceflul unison in a pool. He couldn't imagine anything

less like combat than that. I might not have a world of experi-

ence, he thought, but how could anybody in his right mind

think you could synchronize the confusion and mayhem of any

military operation? It boggled the mind.

"Listen, the prep starts at 1530," came the eventual reply

over the radio, somewhat testily. "Just do it."

"Roger, out," Connors said resignedly. Three bags fulL

Setting in the base of fire and getting the other two squads

in position for the assault was the work of only a few minutes.

Connors checked his watch:

still only a quarter past. Hope

nobody falls asleep waiting, he thought, abundantly aware of

Marines' remarkable ability to doze off on a moment's notice

anytime, anyplace, in any conditions. Fifteen minutes later,

exactly on schedule, the preparation fires commenced and

ended 5 minutes later. Battalion would be pleased: the attack

went flawlessly; there was no enemy resistance to screw it up.

His two squads swept through the tall grass toward the hill

and within minutes were consolidating on the objective.

There was no sign that the enemy had ever occupied the hill.

Whether the enemy was anywhere in the vicinity he couldn't

tell: because of the tall grass, visibility was about 10 yards in

any direction. No matter; they had accomplished the assigned

task.

"Litutenant, company gunny wants our ammo and casualty

report," his radioman said.

26

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

Connors chuckled scornfully. Seeing as there was nobody

to shoot at us and nobody for us to shoot at.

. .

. Now,

Connors, you're being a malcontent again. Just go through

the motions and don 't make waves.

"I'll take it,"

he said, switching on

his headset.

"Hotel-3-Mike, this is 3-Mike-2. No casualties; no ammo ex-

pended. Mission accomplished. What next, over?"

There was pause, then finally the reply came: "Wait out."

1635 Tuesday: "Romeo-2-Oscar, this is 2-Oscar-3."

Capt Takashima recognized the gunny's voice on the com-

mand alternate net. He had been hearing the firefight coming

from that direction for some time now—he didn't know how

long:

it could be 20 minutes, it could be 2 hours—but he

didn't have time to think about it. He'd feel a lot better once

he got the gunny's opinion of the situation.

"This is 2-Oscar, go," Takashima said.

"Confirm situation as described earlier by 2-Oscar-3," Her-

nandez reported. "Engaged, situation well in hand. Echo was

a little slow getting their act together, but Oscar-3 saved their

butts. Caught the enemy pretty good."

"Have you made contact with Echo?"

"Roger," Hernandez said. "Have been attached."

"Say again," Takashima said, confused.

"2-Oscar-3 has been attached to A(pha-7-HoteL"

What the hell? Who the hell does Schuler think he is, tak-

ing it on himself to attach one of my platoons to his company?

Takashima was about to cut loose with some choice words,

27

Command and Control

MCDP 6

but he thought better of it. He knew that he was in no posi-

tion to try to control what third platoon was doing; he was too

busy dealing with the situation at the crossroads. Sometimes

the enemy didn't use the same boundaries that we did, Taka-

shima realized: third platoon was really part of Echo's fight.

That being the case, Takashima knew that for the purposes of

unity of command third platoon ought to be answering to

Schuler and not to him. It was hardly conventional, Taka-

shima decided—certainly not the school solution—but, under

the circumstances, it was the right thing to do. I guess that's

what gunny would call a "self-organizing, complex adaptive

system, "Takashima mused. I'lljust have to remember to give

Schuler a hard time about needing four platoons to do what

we can do with only two.

0255 Wednesday: The MEF commander shed his dripping

poncho as he stepped out of the rain into the MEF command

post. The military policeman snapped to attention and saluted.

"Carry on, Sgt McDavid. Cpl Cooper," he said to his

soaked driver, "get some sleep. It's been a long day."

He made his way into the operations center and dropped

wearily into his chair where he'd started the operation some

24 hours before. In the last 24 hours, he'd been all over the

MEF area of operations. He'd been to the division forward

command post to talk to the division commander face-to-face

about how to deal with the unexpected developments. He'd

insisted on a face-to-face because he wanted to make sure

they understood each other. He'd been to the wing head-

28

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL IMAGE

quarters twice to try to get a handle on the

overall

situation

and to see what could be done about air support. He'd person-

ally debriefed the Cobra pilots who'd first spotted the enemy

column. He'd videotaped a new intent statement—an "intent-

o-mmercial," as the Marines jokingly referred to it—to be

broadcast to the entire MEF (at least down to battalion and

squadron level, the lowest level that had video capability). He

and the wing commander had taken a terrifying V-22 flight

over the battlefield (and unfortunately had gotten precious lit-

tle out of it). He'd been back to the MEF command post once

during the day to see if the situation had gotten any clearer

since he'd left: it hadn't. He'd visited the division's main-

effort regiment and that regiment's main-effort battalion near

Culverin Crossroads. (It hadn't been until he'd met that CO

from Golf Company, Capt Taka-something, and had seen the

indomitable fighting spirit of his Marines that he'd realized

that the MEF would

carry the day—"Just get me some air,

general," the captain had said.) He'd visited the engineers to

make sure that the roads were going to hold up for at least the

next 72 hours in this rain. He'd even spent several hours su-

pervising an assault river crossing during the critical early

stages of the pursuit. And he'd happened upon the FSSG

commander at a maintenance contact point, of all places,

where they'd watched an M1A3 main battle tank repaired and

put back into action; they'd discussed the logistics needed to

support the upcoming exploitation.

It seemed like days since he'd been at the command post.

On the wall screen before him, the amorphous wave of flash-

ing green unit symbols had crept considerably farther north

29

Command and Control

MCDP 6

since the last time he had looked at the map. There were far

more red enemy symbols now as well, most of them encircled

in the lower left-hand part of the screen, an indication that the

intelligence effort had managed to locate many of the enemy

forces that had been unknown at the beginning of the opera-

tion. He knew that many of those units, although still re-

flected on the map and still present on the ground, had ceased

to be effective fighting forces by now. He also knew that the

clean image portrayed on the screen could not begin to cap-

ture the brutal fighting and the destruction that he had wit-

nessed during the day. That was the great danger of being

stuck in a command post, he knew; you began to confuse

what was on a map with reality.

Based on the tempo of activity in the operations center, he

wondered if the staff knew that the battle was all but won. In

the next room, the major and the two staff sergeants who

made up the future plans cell would be working feverishly on

the plans for the next week to exploit the advantage the MEF

had won today. The responsibility of command is never fin-

ished, he decided; always something else to be done. Curi-

ously, he thought, he found himself thinking back to his days

as a brand-new lieutenant at The Basic School, remembering

the adage that had been drilled into them: "Camouflage is

continuous." Command is continuous, he found himself

thinking. I'll have to remember that one, he decided, for the

next time I'm invited to speak at a TBS mess night.

He thought of stopping in to see how things were going in

the future plans cell, but he knew his chief of staff would

have things moving along briskly, and he would just be

MCDP 6

Operation VERBAL iMAGE

getting in the way. Even when the issue had still hung in the

balance, Col Dick Westerby had been pushing the future ops

guys to develop a plan for exploiting the outcome. Around the

MEF command element, Westerby was known with a certain

grudging admiration as "Yesterday," because that was when

he seemed to want everything done. "If it's not done fast,"

Westerby was fond of saying, "it's not done right."

As if by cue, the small, balding colonel appeared, bearing a

cup of steaming coffee.

"You look like you could use this, general," he said.

"Thanks, Dick," the MEF commander said.

A staff sergeant appeared. "Here's the new MEF op order,

colonel," he said, handing a flimsy document to Westerby.

Westerby perused the two-page order which consisted of a

page of text and a diagram, nodding as he read.

"General, do you want to have a look at this?" be asked.

"Hell, no. I couldn't even focus my eyes on it. That's what

I've got you for. You know my intent."

"Looks good, Staff Sergeant Walters," Westerby said, ini-

tialing the document and returning it to the staff sergeant.

"Let's get it out 10 minutes ago."

"Aye, aye, sir; it'll go straight out on the secure fax," Wal-

ters said and quickly departed.

The MEF commander sipped his coffee and gazed at the

large situation screen.

"Well, what do you think, Dick?" he asked.

"What do I think?" Westerby said. "I think we went in

with an unclear picture of the situation, and it only got worse.

As is usually the case, the enemy tended not to cooperate.

Command and Control

MCDP 6

Weather precluded using the bulk of our aviation and re-

stricted the mobility of some of our vehicles. Our original

plan had to be quickly discarded and another put in its place.

We had to adapt to a rapidly changing situation. Our previous

planning efforts provided us with the flexibility and situa-

tional awareness to react to a changing situation and provided

flexibility to our subordinates. Thank goodness for staff offi-

cers, pilots, and subordinate commanders who exercise initia-

tive and quickly adapt to changing situations."

"Yes," the general said with obvious satisfaction, "don't

you love it when the system works to perfection?"

32

Chapter 1

The Nature

of

Command and Control

"War is the realm of uncertainty, three quarters of the factors

on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of

greater or lesser uncertainly... .

The commander must work

in a medium which his eyes cannot see; which his best deduc-

tive powers cannot always fathom; and with which, because

of constant changes, he can rarely become familiar."

—Carl von Clausewitz

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

T

o put effective command and control into practice, we

must first understand its fundamental nature—its pur-

pose, characteristics, environment, and basic functioning.

This understanding will become the basis for developing a

theory and a practical philosophy of command and control.

How IMPORTANT IS COMMAND AND CONTROL?

No single activity in war is more important than command

and control. Command and control by itself will not drive

home a single attack against an enemy force. It will not de-

stroy a single enemy target. It will not effect a single emer-

gency resupply. Yet none of these essential warfighting

activities, or any others, would be possible without effective

command and control. Without command and control, cam-

paigns, battles, and organized engagements are impossible,

military units degenerate into mobs, and the subordination of

military force to policy is replaced by random violence. In

short, command and control is essential to all military opera

tions and activities.

With command and control, the countless activities a mili-

tary force must perform gain purpose and direction. Done

well, command and control adds to our strength. Done poorly,

it invites disaster, even against a weaker enemy. Command

and control helps commanders make the most of what they

35

Command and Control

MCDP 6

have—people, information, material, and, often most impor-

tant of all, time.

In the broadest sense, command and control applies far be-

yond military forces and military operations. Any system

comprising multiple, interacting elements, from societies to

sports teams to any living organism, needs some form of

command and control. Simply put, command and control in

some form or another is essential to survival and success in

any competitive or cooperative enterprise. Command and

control is a fundamental requirement for life and growth, sur-

vival, and success for any system.

WHAT IS COMMAND AND CONTROL?

We often think of command and control as a distinct and

specialized function—like logistics, intelligence, electronic

warfare, or administration—with its own peculiar methods,

considerations, and vocabulary, and occurring independently

of other functions. But in fact, command and control encom-

passes all military functions and operations, giving them

meaning and harmonizing them into a meaningful whole.

None of the above functions, or any others, would be pur-

poseful without command and control. Command and control

36

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

is not the business of specialists—unless we consider the

commander a specialist—because command and control is

fundamentally the business of the commander.'

Command and control is the means by which a commander

recognizes what needs to be done and sees to it that appropri-

ate actions are taken. Sometimes this recognition takes the

form of a conscious command decision—as in deciding on a

concept of operations. Sometimes it takes the form of a pre-

conditioned reaction—as in immediate-action drills, practiced

in advance so that we can execute them reflexively in a mo-

ment of crisis. Sometimes it takes the form of a rules-based

procedure—as in the guiding of an aircraft on final approach.

Some types of command and control must occur so quickly

and precisely that they can be accomplished only by comput-

ers—such as the command and control of a guided missile in

flight. Other forms may require such a degree of judgment

and intuition that they can be performed only by skilled, ex-

perienced people-as in devising tactics, operations, and

strategies.

Sometimes command and control occurs concurrently with

the action being undertaken—in the form of real-time guid-

ance or direction in response to a changing situation. Some-

times it occurs beforehand and even after. Planning, whether

rapidltime-sensitive or deliberate, which determines aims and

objectives, develops concepts of operations, allocates re-

sources, and provides for necessary coordination, is an impor-

tant element of command and control. Furthermore, planning

37

Command and Control

MCDP 6

increases knowledge and elevates situational awareness. Ef-

fective training and education, which make it more likely that

subordinates will take the proper action in combat, establish

command and control before the fact. The immediate-action

drill mentioned earlier, practiced beforehand, provides com-

mand and control. A commander's intent, expressed clearly

before the evolution begins, is an essential part of command

and control. Likewise, analysis after the fact, which ascertains

the results and lessons of the action and so informs future ac-

tions, contributes to command and control.

Some forms of command and control are primarily proce-

dural or technical in nature—such as the control of air traffic

and air space, the coordination of supporting arms, or the fire

control of a weapons system. Others deal with the overall

conduct of military actions, whether on a large or small scale,

and involve formulating concepts, deploying forces, allocat-

ing resources, supervising, and so on. This last form of com-

mand and control, the overall conduct of military actions, is

our primary concern in this manual. Unless otherwise speci-

fied, it is to this form that we refer.

Since war is a conflict between opposing wills, we can

measure the effectiveness of command and control only in re-

lation to the enemy. As a practical matter, therefore, effective

command and control involves protecting our own command

and control activities against enemy interference and actively

monitoring, manipulating, and disrupting the enemy's com-

mand and control activities.

38

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

WHAT IS THE BASIS OF COMMAND AND

CONTROL?

The basis for all command arid control is the authority vested

in a commander over subordinates. Authority derives from

two sources. Official authority is a function of rank and posi-

tion and is bestowed by organization and by law. Personal

authority is a function of personal influence and derives from

factors such as experience, reputation, skill, character, and

personal example. It is bestowed by the other members of the

organization. Official authority provides the power to act but

is rarely enough; most effective commanders also possess a

high degree of personal authority. Responsibility, or account-

ability for results, is a natural corollary of authority. Where

there is authority, there must be responsibility in like meas-

ure. Conversely, where individuals have responsibility for

achieving results, they must also have the authority to initiate

the necessary actions.2

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSIIIP BETWEEN

"COMMAND" AND "CONTROL"?

The traditional view of command and control sees "com-

mand" and "control" as operating in the same direction: from

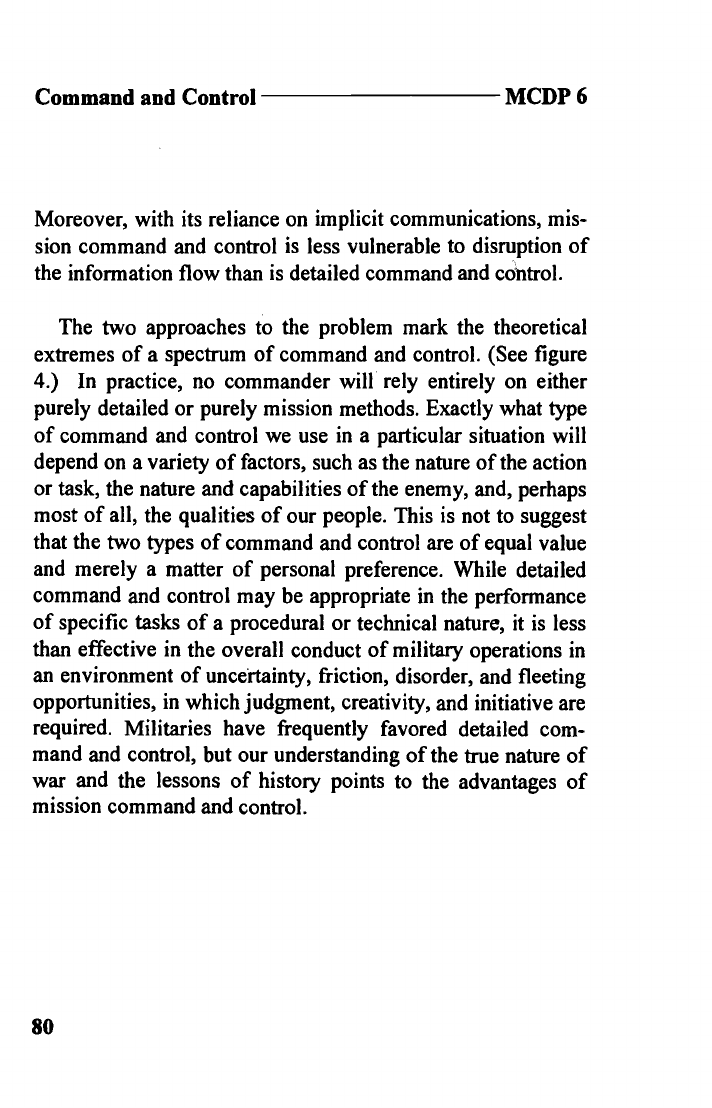

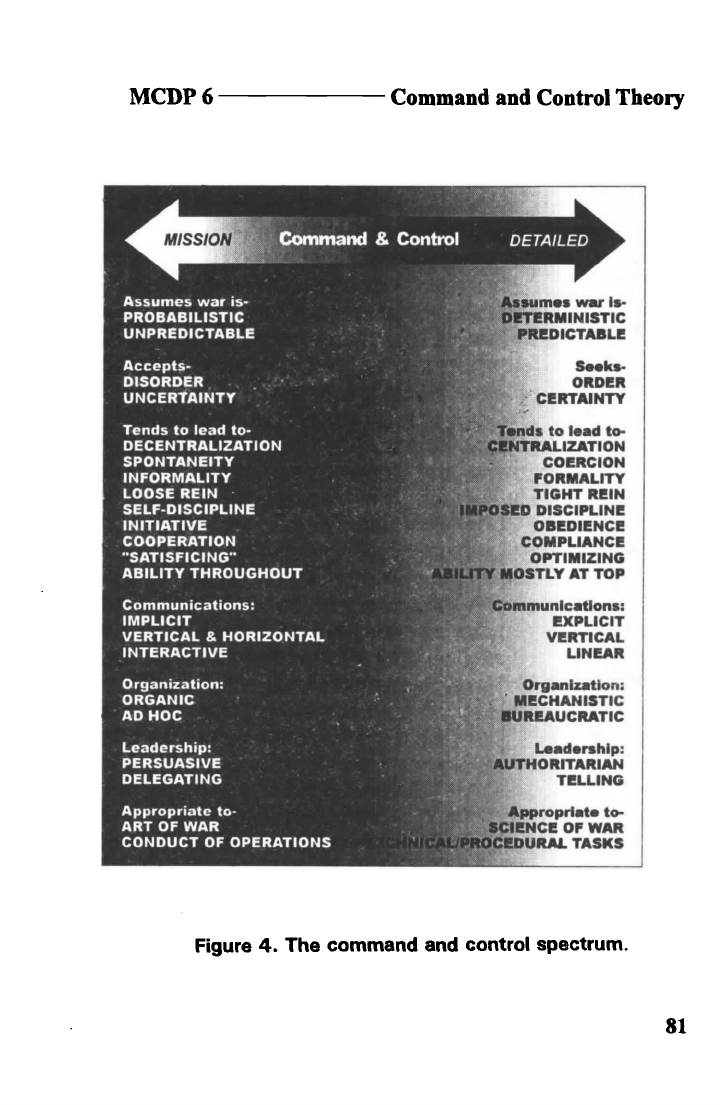

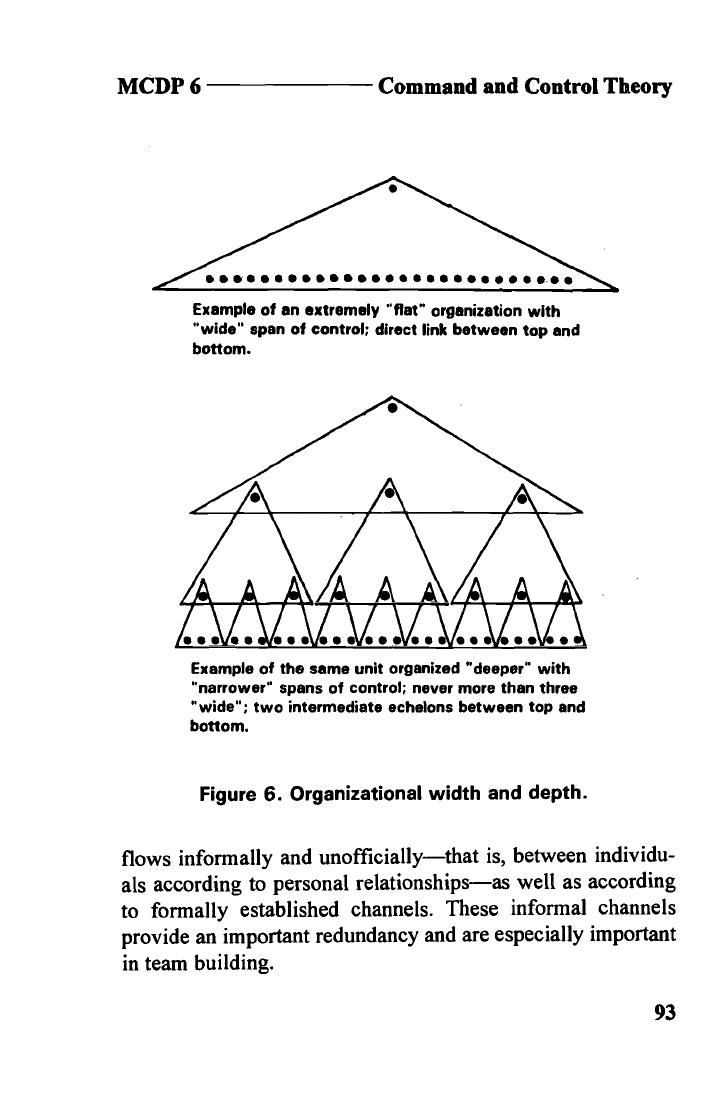

the top of the organization toward the bottom.3 (See figure 1.)

Commanders impose control on those under their command;

39

Command and Control

MCDP 6

commanders are "in control" of their subordinates, and subor-

dinates are "under the control" of their commanders.

We suggest a different and more dynamic view of com-

mand and control which sees command as the exercise of

authority and control as feedback about the effects of the ac-

tion taken. (See figure 1.) The commander commands by de-

ciding what needs to be done and by directing or influencing

the conduct of others. Control takes the form of feed-

back—the continuous flow of information about the unfold-

ing situation returning to the commander—which allows the

commander to adjust and modify command action as needed.

Feedback indicates the difference between the goals and the

situation as it exists. Feedback may come from any direction

and in any form—intelligence about how the enemy is react-

ing, information about the status of subordinate or adjacent

units, or revised guidance from above based on develop-

ments. Feedback is the mechanism that allows commanders

to adapt to changing circumstances—to exploit fleeting op-

portunities,

respond

to

developing problems,

modify

schemes, or redirect efforts. In this way, feedback "controls"

subsequent command action. In such a command and control

system, control is not strictly something that seniors impose

on subordinates; rather, the entire system comes "under con-

trol" based on feedback about the changing situation.4

Command and control is thus an interactive process in-

volving all the parts of the system and working in all direc-

tions. The result is a mutually supporting system of give and

40

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

A typical view of com-

mand and control—com-

mand and control seen

as unidirectional.

Command and control

viewed as reciprocal in-

fluence—command as

initiation of action and

control as feedback.

Figure 1. Two views of the relationship

between command and control.

take

in which complementary commanding and controlling

forces interact to ensure that the force as a whole can adapt

continuously to changing requirements.

COMMANDER

I COMMANDER

I

I COMMANDER

COMMANDER

I—

Command and Control

MCDP 6

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE "IN CONTROL"?

The typical understanding of effective command and control

is that someone "in command" should also be "in control."

Typically, we think of a strong, coercive type of command

and control—a sort of pushbutton control—by which those

"in control" dictate the actions of others and those "under

control" respond promptly and precisely, as a chess player

controls the movements of the chess pieces. But given the na-

ture of war, can commanders control their forces with any-

thing even resembling the omnipotence of the chess player?

We might say that a gunner is in control of a weapon system

or that a pilot is in control of an aircraft. But is a flight leader

really directly in control of how the other pilots fly their air-

craft? Is a senior commander really in control of the squads

of Marines actually engaging the enemy, especially on a mod-

ern battlefield on which units and individuals will often be

widely dispersed, even to the point of isolation?

We are also fond of saying that commanders should be "in

control" of the situation or that the situation is "under con-

trol." The worst thing that can happen to a commander is to

"lose" control of the situation. But are the terrain and weather

under the commander's control? Are commanders even re-

motely in control of what the enemy does? Good comm and-

ers may sometimes anticipate the enemy's actions and may

even influence the enemy's actions by seizing the initiative

and forcing the enemy to react to them. But it is a delusion to

42

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

believe that we can truly be in control of the enemy or the

situation.5

The truth is that, given the nature of war, it is a delusion to

think that we can be in control with any sort of certitude or

precision. And the further removed commanders are from the

Marines actually engaging the enemy, the less direct control

they have over their actions. We must keep in mind that war

is at base a human endeavor. In war, unlike in chess, "pieces"

consist of human beings, all reacting to the situation as it per-

tains to each one separately, each trying to survive, each

prone to making mistakes, and each subject to the vagaries of

human nature. We could not get people to act like mindless

robots, even if we wanted to.

Given the nature of war, the remarkable thing is not that

commanders cannot be thoroughly in control but rather that

they can achieve much influence at all. We should accept that

the proper object of command and control is not to be thor-

oughly and precisely in control. The turbulence of modem

war suggests a need for a looser form of influence—some-

thing that is more akin to the willing cooperation of a basket-

ball team than to the omnipotent direction of the chess

player—that provides the hecessary guidance in an uncertain,

disorderly, time-competitive environment without stifling the

initiative of subordinates.

43

Command and Control

MCDP 6

COMPLEXITY IN COMMAND AND CONTROL

Military organizations and military evolutions are complex

systems. War is an even more complex phenomenon—our

complex system interacting with the enemy's complex system

in a fiercely competitive way. A complex system is any sys-

tem composed of multiple parts, each of which must act indi-

vidually according to its own circumstances and which, by so

acting, changes the circumstances affecting all the other parts.

A boxer bobbing and weaving and trading punches with his

opponent is a complex system. A soccer team is a complex

system, as is the other team, as is the competitive interaction

between them. A squad-sized combat patrol, changing forma-

tion as it moves across the terrain and reacting to the enemy

situation, is a complex system. A battle between two military

forces is itself a complex system.6

Each individual part of a complex system may itself be a

complex system—as in the military, in which a company con-

sists of several platoons and a platoon comprises several

squads—creating multiple levels of complexity. But even if

this is not so, even if each of the parts is fairly simple in it-

self, the result of the interactions among the parts is highly

complicated, unpredictable, and even uncontrollable behav-

ior. Each part often affects other parts in ways that simply

cannot be anticipated, and it is from these unpredictable inter-

actions that complexity emerges. With a complex system it is

usually extremely difficult,

if not impossible, to

isolate

44

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Contro'

individual causes and their effects since the parts are all con-

nected in a complex web. The behavior of complex systems is

frequently nonlinear which means that even extremely small

influences can have decisively large effects, or vice versa.

Clausewitz wrote that "success is not due simply to general

causes. Particular factors can often be decisive—details only

known to those who were on the spot.

. . while issues can be

decided by chances and incidents so minute as to figure in

histories simply as anecdotes."

The element of chance, in-

teracting randomly with the various parts of the system, intro-

duces even more complexity and unpredictability.

It is not simply the number of parts that makes a system

complex:

it is the way those parts interact. A machine can be

complicated and consist of numerous parts, but the parts gen-

erally interact in a specific, designed way—or else the ma-

chine will not function. While some systems behave mech-

anistically, complex systems most definitely do not. Complex

systems tend to be open systems, interacting frequently and

freely with other systems and the external environment. Com-

plex systems tend to behave more "organically"—that is,

more like biological organisms.8

The fundamental point is that any military action, by its

very nature a complex system, will exhibit messy, unpredict-

able, and often chaotic behavior that defies orderly, efficient,

and precise control. Our approach to command and control

must find a way to cope with this inherent complexity. While

a machine operator may be in control of the machine, it is

45

Command and Control

MCDP 6

difficult to imagine any commander being in control of a

complex phenomenon like war.

This view of command and control as a complex system

characterized by reciprocal action and feedback has several

important features which distinguish it from the typical view

of command and control and which are central to our ap-

proach. First, this view recognizes that effective command

and control must be sensitive to changes in the situation. This

view sees the military organization as an open system, inter-

acting with its surroundings (especially the enemy), rather

than as a closed system focused on internal efficiency. An ef-

fective command and control system provides the means to

adapt to changing conditions. We can thus look at command

and control as a process of continuous adaptation. We might

better liken the military organization to a predatory ani-

mal—seeking information, learning, and adapting in its quest

for survival and success—than to some "lean, green ma-

chine." Like a living organism, a military organization is

never in a state of stable equilibrium but is instead in a con-

tinuous state of flux—continuously adjusting to

its sur-

roundings.

Second, the action-feedback loop makes command and

control a continuous, cyclic process and not a sequence of

discrete actions—as we will discuss in greater detail later.

Third, the action-feedback loop also makes command and

control a dynamic, interactive process of cooperation. As we

have discussed, command and control is not so much a matter

46

MCDP 6

The Nature of Command and Control

of one part of the organization "getting control over" another

as something that connects all the elements together in a co-

operative effort. All parts of the organization contribute ac-

tion and feedback—"command" and "control"—in overall